Encountering Culture: A Dialogue

Out of Place

Atonement

Lost in Translation

Displaced Objects

Wind in Utopia

Habitat: A Question of Place

![]()

Out of Place (2001-02)

Out of Place is a project about the specifics of place and the particularities of location, Alice Springs/Central Australia, a geographical location loaded in history, symbolism, and an archive of political and social analyses—framing a historically contested site. One immediately enters into the dynamics and discourses of binary Australia: nature/culture, colonial/postcolonial, Indigenous/non-Indigenous, resemblance/non-resemblance, masculinity/femininity, fear/desire, and so forth. Issues of representation/non-representation, possession/dispossession, silence/resistance, visibility/invisibility come into historical play and replay: the troubled mappings of our colonial past.

Alice Springs is a bi-cultural township. Aboriginal families have been permanent residents since time immemorial, in spite of successive epochs of destructive governmental policies. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak states that culture alive is its own irreducible counter-culture. She also states that culture is a space of collision.

Out of Place comprises of three distinct interpellations about place: Pool, Stereoscopic Histories, and Summer Rains. Pool is a suite of 28 photographic prints (each print 78.0cm x 108.0cm) taken at the local Alice Springs municipal pool during the summer months of January - March 1999. Stereoscopic Histories is a series of 8 works or 4 diptychs each 108.0cm x 108.0cm in size. These works entertain the colonial impulse to name, describe, identify, and claim. Summer Rains is a suite of 12 large-scale photographic prints (or four epic works) each representing large tracts of country. Each work is made up of 3 panels (measuring 105.0cm x 250.0cm and 127.0cm x 250.0cm) or, combined, 315.0cm x 250.0cm approximately. This suite of work represents the cyclic nature of summer and is entitled, December, January, February, and March.

Images left:

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001-02)

Lightjet digital photographic print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Publications

landscape.country

(Chris Barry)Stereoscopic Histories

(Chris Barry)Links

Gertrude

Contemporary:

Chris Barry (Past

Studio Artist)Adam Art Gallery/

Te Pataka Toi

Victoria University, Wellington

National Library of

Australia

--Catalogue:

landscape.country

Pool

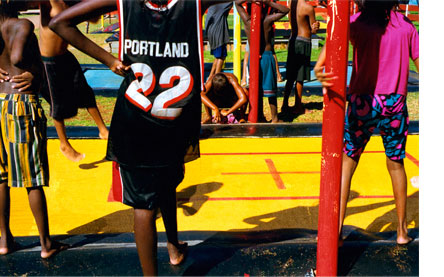

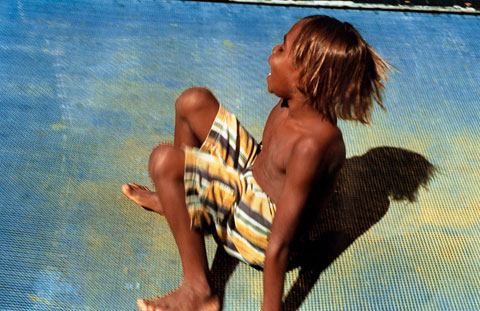

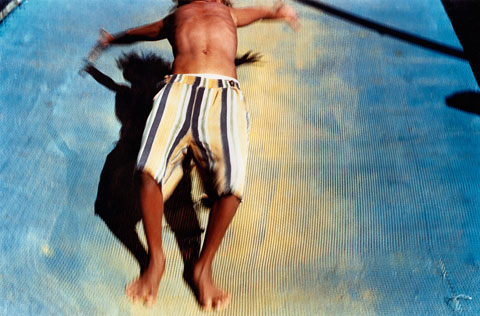

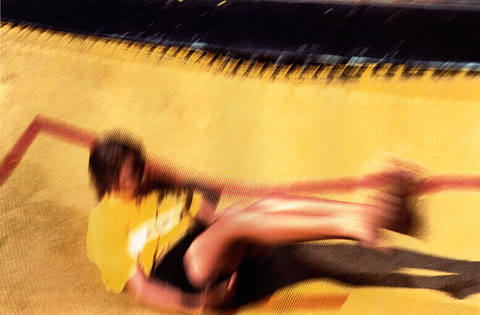

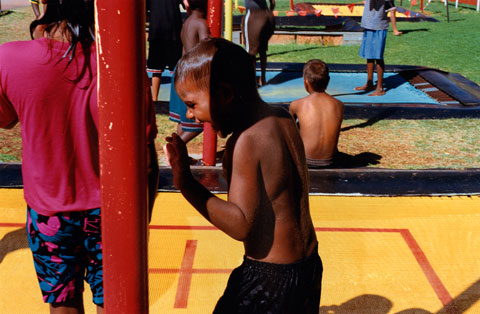

Pool is a suite of 28 photographic prints (each print 78.0cm x 108.0cm) taken at the local Alice Springs municipal pool during the summer months of January - March 1999. Pool celebrates the vibrancy and agency of Aboriginal life worlds, the currency and vitality of culture in situ. By using colour and rhythm, motion and stasis, pattern and repetition, identity politics are examined and performed through the physicality of bodies, shapes, and gravity. Their arrangement and re-arrangement, in motion or stilled, in-frame and out-of-frame, signify performative gestures of strength, tenacity, agility and resilience—those qualities associated with resistance and survival. The body becomes a contemporary palimpsest re-inscribing itself into place—claiming legitimacy, visibility, prominence and representation. The body as inscriptive surface, historical site-marker, and sensual proof, is re-written into space and time and situated within the specificity of location. A tacit narrative of place and people is told through a framework of physical presence, performative gesture, and the arrangement of colour and shape.

The local municipal pool entertains children and teenagers from multifarious language groups and communities—Yuendumu, Papunya, Kintore, Utopia, Ernabella, Fregon, Amata, etc. Local kids represent a cross-section of town camps, housing estates, township flats, and near-by traditional lands situated on the outskirts of Alice Springs. Yirara College, the local Lutheran boarding school, is a frequent pool regular. However, most of the children photographed in Pool are family and kin from Morris Soak, a town camp on the western outskirts of Alice Springs, together with their town relatives. Morris Soak is a mixture of Arrernte and Luritja language groups. Historically this is the camp where Albert Namatjira and his kin lived.

Image above:

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001-02)

Lightjet digital photographic print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Image above:

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001-02)

Lightjet digital photographic print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Image left:

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001-02)

Lightjet digital photographic print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Image left:

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001-02)

Lightjet digital photographic print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Image left:

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001-02)

Lightjet digital photographic print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Image left:

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001-02)

Lightjet digital photographic print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

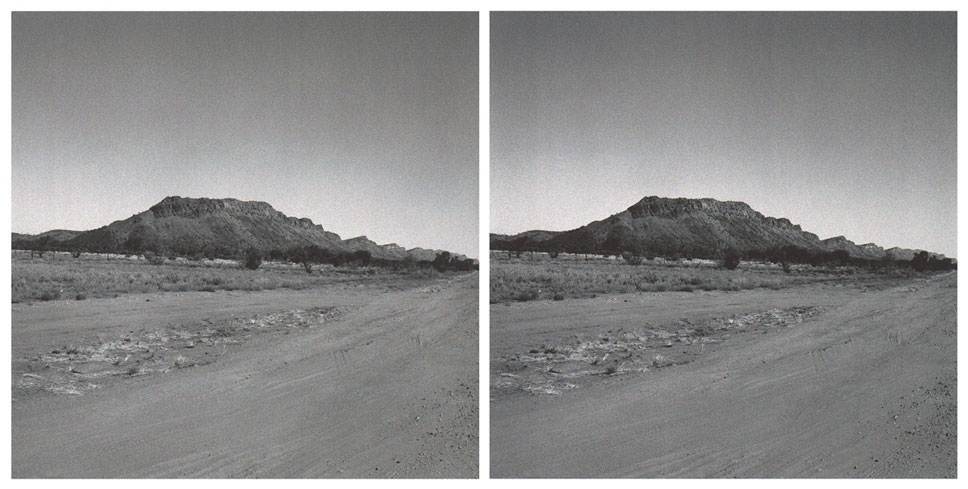

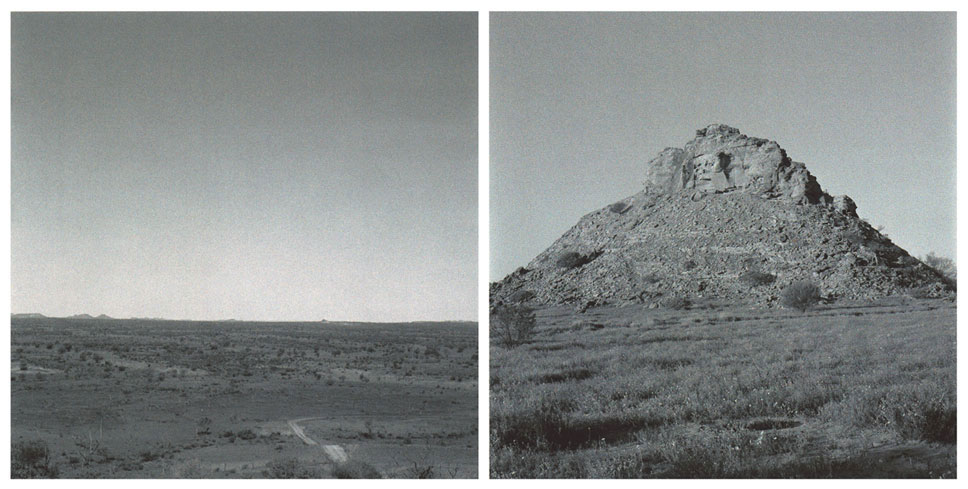

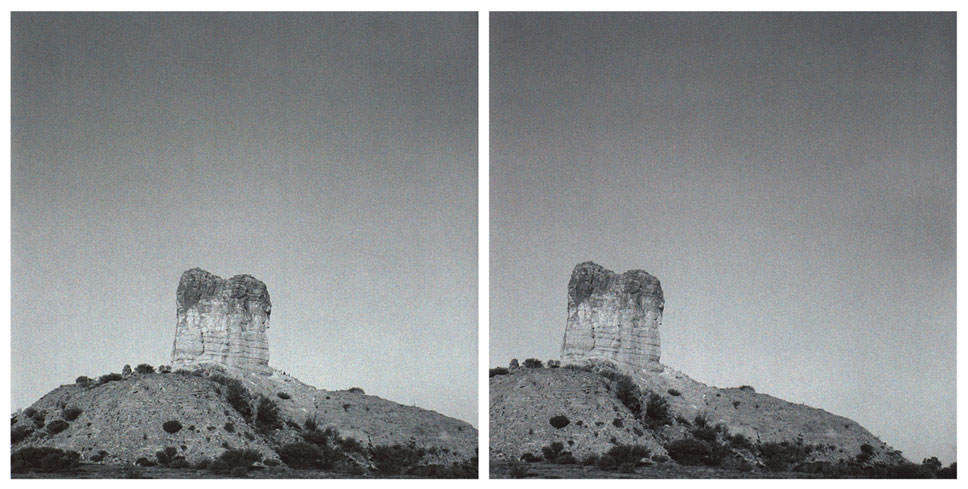

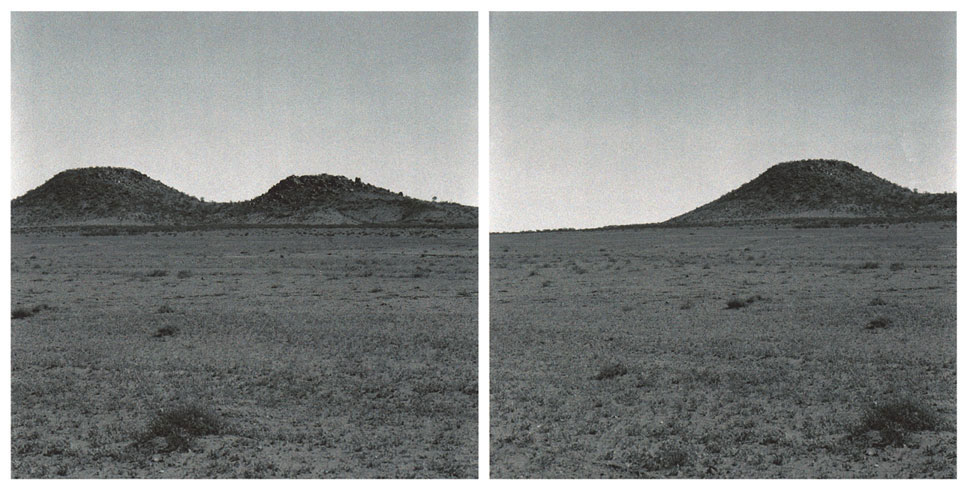

Stereoscopic Histories

Stereoscopic Histories is a series of 8 works or 4 diptychs each 108.0cm x 108.0cm in size. These works entertain the colonial impulse to name, describe, identify, and claim. According to the Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary (1972), the stereoscope is “an instrument by which the images of two pictures differing slightly in point of view are seen one by each eye and so give an effect of solidarity”. These works, then, signal two differing perspectives and offer two differing knowledge systems. A European subjectivity is imposed onto a place and culture other to itself—and the struggle over geography continues into the present. To the colonial gaze this is a place that lacks description, contains no identifiable European markers, defies European concepts of the picturesque, and threatens resemblance and familiarity. The unbounded nature of this country remains empty, extreme, and barren to the eye. Disorientation, formlessness, and unfamiliarity challenge a European belonging and sensibility. The doubling of the images suggests the narcissistic nature of the coloniser’s gaze—“where often all they could see in the distance was a mirage resembling the illusion of their own presence”—their own solipsism reflecting back on itself (Carter, 1987). They remain incapable of stepping out of their own subjective self and arriving into the space of the Other. And, it is in this context, that the oral and spatial history of Aboriginal Australia is made mute. Aborigines are perceived, and continue to be seen, as loitering on the edge of our historical clearing.

This work, however, does not simply illustrate a European colonial reading—it also points to another form of occupation. The stereoscopic nature of the work—inducing the cognitive act of looking and of imaging—fails to deliver attachment. The inability and inaccessibility to position oneself within this country suggests a non-relationship to place, rather than one of belonging and attachment. This knowledge belongs to a prior history and people. The stillness, the spatiality, and the formalism inherent, suggests a position of resistance—the impulse and desire to return the coloniser’s gaze. It reminds the viewer that this country has been formed and inhabited by other ancestors and ancestral beings, other presences, and belongs to a complex continuum other to recent European settlement. Even my own presence in this landscape, and the imaging of it, falls into a formlessness; there are no boundaries or edges to explain or define my own perspective. My only framing device is the perimeters of my viewfinder (a square format Bronica camera), the metal dimensions of my car window, or open car door, or the vicarious fragments of country caught in my rear view mirror—insufficient and transient devices for capturing understanding and a knowledgeable comprehension of place.

Image above:

Chris Barry

Stereoscopic Histories

Out of Place

Digital photographic print

108.0cm x 108.0cm

each print

Image above:

Chris Barry

Stereoscopic Histories

Out of Place

Digital photographic print

108.0cm x 108.0cm

each print

However there is another possibility for engagement and encounter, one that is more akin to an Indigenous realisation of place—a relationship through the body. Stereoscopic Histories not only signals Indigenous custodianship, it also makes reference to a feminine interpretation and sensibility—sensuousness—one that critiques the male heroics of exploration myths and frontier settlement. This work is sensual, tactile, textured, and sexualised in its imaging. It signals the female hand at play and a female presence in what is generally seen as a white male-dominated landscape. The absent female is symbolically re-inscribed into place and situated akin to an Indigenous relationship to country—where both men and women hold equal custodianship and gender-specific responsibilities over inherited ancestral estates. Aboriginal culture is sensual, tactile, textured, and sexualised within its own cultural materiality, and, as Marcia Langton states, “sensual proof” of its law and sense of place. In stark contrast, European explorer narratives view the frontier landscape as either the mistress to possess and conquer, or the bad mother: infertile and one to be feared and loathed (Gibson, Camera Natura).

This series of landscape photographs were taken during my first trip to Alice Springs and Central Australia in 1994. My knowledge of country and culture was embryonic; my relationship to place, new and unknowable. The difference, the vastness, the remoteness, the scale, the space, the climate, the fearing, the desiring, the romanticising—all become part of a “repertoire of arrival” and other to the subjective self. This experience is repeated all over again when one encounters and enters into Aboriginal culture. My own fearing and desiring of this country, and its attendant Indigenous cultures, is hidden within this colonial/postcolonial framework. The empirical struggle over geography is mimicked by my own struggle into geography. To produce work within the colonial/postcolonial framework seemed a valid and safe beginning. It would take a long time to lose one’s self-consciousness with place and develop a knowledge and understanding in place—to learn a whole other knowledge system. Personally, Stereoscopic Histories developed into a satisfying conceptual form, one that enabled not only the possibility for a historic overview of place, but a point of entry into place. My own physical presence is compounded by a dense and traumatic historical context. I arrive after the fact and have to negotiate my way through this complex and contradictory historical paradigm—a virtual historic and cultural minefield.

© Chris Barry, 2002

Image above:

Chris Barry

Stereoscopic Histories

Out of Place

Digital photographic print

108.0cm x 108.0cm

each print

Image above:

Chris Barry

Stereoscopic Histories

Out of Place

Digital photographic print

108.0cm x 108.0cm

each print

Summer Rains

Summer Rains is a suite of 12 large-scale photographic prints (or four epic works) each representing large tracts of country. Each work is made up of 3 panels (measuring 105.0cm x 250.0 and 127.0cm x 250.0cm) or, combined, 315.0cm x 250.0cm approximately. This suite of work represents the cyclic nature of summer and is entitled, December, January, February, and March. (December to March is the hottest time in Central Australia, as well as being the time of “business” for most Aboriginal language groups and their communities). Each panel is made up of hundreds of taut bras stretched across a flat plane field. This work refers to the symbolic transformation of country from parched, dry, yellow grasses (December) into the lush, green, and prolific living environment of life after the rains (March). The work insinuates the fecundity and fertility produced by exceptional rains, particularly after prolonged periods of little or no water. In Aboriginal life ways, stagnation is followed by fertility and the anticipation of bush foods, representing benevolence, nourishment, and continuity. Vast volumes of water flow into creek beds and rivers, permanent waterholes replenish, clay pans retain surface water for several months at a time, and temporary and permanent waterholes flourish and provide relief from the heat.

The materiality of the bras and their arrangement mimic the rhythms, patterns, and colours found in the landscape itself. The undulations, the rock formations, the cascading movements found in waterholes, ridges, and ranges, compressed rock beds and geological strata’s, the lyrical movement of grasses, bushes, and leaves, fields of hairy, yellow Spinifex that move in the wind, and the long summer Buffel grasses, sometimes one meter in height. These prolonged rains eventually transform a seemingly arid landscape into a dense, lush and verdant green.

This work is sensuous and sexualised, both within its own materiality, and within the multiplicity and potency found in its repetition and profusion. Abject bras are dyed new and stretched over a historic male landscape that has dominated the European imagination and its relationship to history and place. The lyricism and musicality is other to conventional representations of frontier settlement and the absent female is made present through sensual form and rhythmic patterns: the connection between body and place—the site of experience, the container of memory, sensor and receptor. The body is re-inscribed into space and time and is situated within the specifics of its location: the poetics and politics of place.

Image above:

Chris Barry

Summer Rains (December)

Out of Place

Lightjet digital photographic print

105.0cm x 250.0cm

each print

Image above:

Chris Barry

Summer Rains (January)

Out of Place

Lightjet digital photographic print

105.0cm x 250.0cm

each print

These works also signal the climatic changes experienced during the summer months. This is the time of the Big Wet created by a succession of tropical cyclones that work their way south into the Central and Western Desert region. It is a time of extreme heat, atmospheric build-up, humidity, spectacular electrical storms, thunderstorms, torrential rains, flooding, and then the inevitable return of heat once again.

My initial and subsequent returning to Alice Springs/Central Australia (1993–2004) is a summer relationship to place—experienced through the body. The body, stripped of all clothing, sweats, heats up, dehydrates, expires, cools off, replenishes. Dries out in heat, softens in moisture, revitalises in water. Arrives white and flabby, turns dark brown and robust. It maintains a direct relationship to country and climate. In effect, Summer Rains reflects and re-inscribes my own presence in space and time, and re-creates my own autobiographical trajectory into place.

Image above:

Chris Barry

Summer Rains (February)

Out of Place

Lightjet digital photographic print

127.0cm x 250.0cm

each print

Summer Rains, like Stereoscopic Histories, reinstates a feminine ethos. These works aspire towards an Aboriginal understanding of place, wherein country and body are considered intrinsic and inseparable, where one ultimately re-inscribes the other. This is a culture based on the inter-relatedness between all things—flora and fauna, country, weather, community, events, and happenings, are all seen as one entity wherein each aspect of culture informs the other. These are played out in ceremonies, performances, songs, and storytelling, and can be read in ceremonial markings on bodies, cultural artefacts, and the cartographies often illustrated in contemporary painting practices. Stories are illustrated on the body, performed and ritualised, told orally, sung, or drawn on the ground, onto canvas, or onto bark. This ethos also extends into the spiritual realm, where time is recognised as a continuum: the sum parts of the present, the past, and the future. Similarly life forms exist underground, on the ground, and as extra-terrestial beings. Life is seen as one, ‘the lot’ or awelye, that is, as a continuum.

Summer Rains is a body of work that embellishes inter-cultural and inter-subjective engagement. This time, however, Aboriginal culture and life worlds impact onto a European female presence. Through direct contact and the imparting of local knowledge over a long period of time, one participates in a form of cultural imbrication—an Aboriginal overlapping that produces a new mutual space from which to share, exchange, and exist in. However, this inter-subjective space is one of acknowledgement for, and respect of, a knowledge system that has existed and survived over, and through, European contact and settlement. This work is an acknowledgement of an Aboriginal presencing that exists as a continuum—past, present and future—awelye, or, the lot, as cited by Emily Kame Kngwarreye.

© Chris Barry, 2002

Image above:

Chris Barry

Summer Rains (March)

Out of Place

Lightjet digital photographic print

127.0cm x 250.0cm

each print

Pool

Out of Place (2001-02)This Aboriginal sociality captured on the trampolines has practically disappeared. Pool effectually recorded a time when children could play together in an unregulated and unrestricted manner, and, in this case, fitting into an Aboriginal collective ethos based on extensive skin networks. These mesh trampolines were effectively the original ones installed at the same time when the pool was first constructed (c.1970s). In the following year, these old trampolines were replaced by two black rubber versions that complied with the newly imposed strictures of public liability. These regulations enforced single occupancy and illustrated the ‘individuated’ behaviour desired by western standards, and one that was highly monitored and regulated by pool staff. Needless to say, these trampolines have now disappeared completely. Interestingly, these photographs have become a historic record of another time in the history of the municipal pool, one that captured an Aboriginal collective ethos and sociality being played out and performed in a public utility.

Image above:

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001–02)

Lightjet photographic digital print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001–02)

Lightjet photographic digital print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Click images to enlarge

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001–02)

Lightjet photographic digital print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Click images to enlarge

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001–02)

Lightjet photographic digital print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Click images to enlarge

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001–02)

Lightjet photographic digital print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Click images to enlarge

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001–02)

Lightjet photographic digital print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Click images to enlarge

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001–02)

Lightjet photographic digital print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Click images to enlarge

Images above and left:

Chris Barry

Pool

Out of Place (2001–02)

Lightjet photographic digital print

78.0cm x 108.0cm

Click images to enlarge

Installations

RMIT Gallery/RMIT University, Melbourne (2001)

Griffith University Art Gallery/Griffith University, Brisbane (2002)

Adam Art Gallery -Te Pataka Toi/Victoria University, Wellington NZ (2002)

Acknowledgements:

Erica Franey and Micky, Julie, Clifford, Charmaine, and Michael Woodford;

Vera, Frank, Lucky-Luke and Bradley Curtis;

Valerie Curtis, Craig and Corey McDowell;

Paula Perkins and Paula Lawton;

Jennifer, Richard, and Jethro Forbes;

Karen, Shane, and Shane-Shane Franey;

Audrey McCormick, Daryl and Darelle Taylor;

Noeline Minarri and family;

Julie Coultarde and family;

Mervyn Franey and Diane Curtis and Russell and Brian Franey.